Plan Well, Paint Fast: The Process of Watercolorist Andy Evansen

Minnesota with its frozen winters and summers dripping with humidity, is not the land we think of as the birthplace to plein air painters.

But watercolorist Andy Evansen (Ep. 12), a Minnesota resident, was working as a medical illustrator and realized two things: First, his favorite painters-namely painted outside and second, that as an artist, he wanted to be able to tackle anything.

So Evansen packed up his paints and headed outdoors.

“That was a disaster,” Evansen says of his first year painting outside, or plein air. “I mean, it’s still a disaster more than half the time. It’s really really tough.”

A CHANGING APPROACH

The challenge of painting plein air has been taken on by artists since pigment technology allowed artists to leave their studios. It has also changed the way painters paint.

For Evansen, it forced him to figure out a way of working that was economical.

He looked again to his idols for guidance.

“I started looking at books of the British watercolorists or studied their work and really focused on the way they simplify the landscape.”

Evansen loved how Trevor Chamberlain, in particular, combined soft and hard edges in his scenes. He also admired how Chamberlain had traveled the world and no matter what he painted, you could tell it was a Chamberlain piece.

“I really started to focus in - not so much on colors and subjects matter- but the way [the British painters] handled washes and shapes.”

THE POWER OF SIMPLICITY

Evansen’s process- and the one his students travel to learn - is value and shape driven. But it starts with simplicity. And while he no longer paints exclusively outdoors, what plein air taught him remains, namely the importance of a plan and simplifying.

Simplifying is the biggest challenge he sees his students facing. As a teacher, Evansen asks his students to bring their own reference photos to his workshops so that they can problem solve them together.

And the photos they bring do need some problem solving.

“They pull out their photos [and] I’m like Good Lord. I wouldn’t even try and tackle that.”

The photos are much too complicated. In the workshop, Evansen will show them how to crop the reference down to about an eighth of the original photo.

Evansen understands the struggle.

“I’m still guilty of it too from time to time,” he says. “It’s hard to leave stuff out. The world is pretty.”

He reminds himself and his students that, yes, everything in the photo is beautiful, but that they are painting a painting. That’s their goal. Their goal isn’t to replicate the whole world.

For Evansen, when he looks at a scene, we will decide a few things he wants the painting to be about. He then will work towards that as his area of interest.

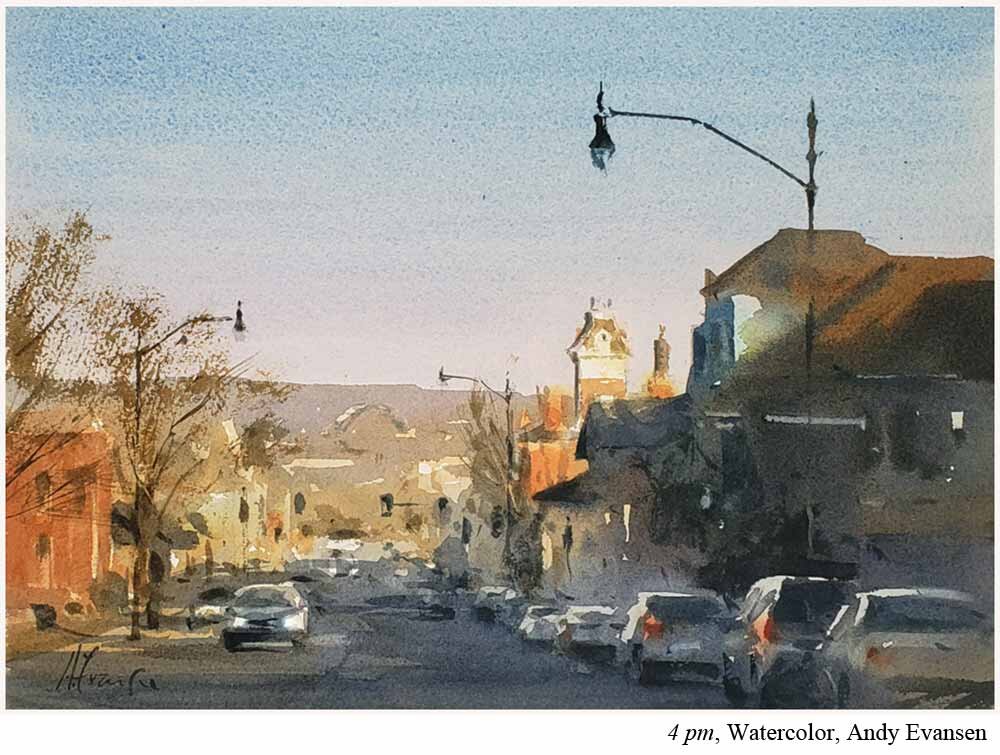

Evansens believes that knowing what is (and what is not) the story you want to convey to your audience is critical. Maybe it’s light on a steeple. A group of people gathering. Whatever it is, know it, and use value primarily to help you tell it.

“It’s so important to remember why did I set up the painting here. Why did I choose this photo? And make sure your decision making is all about reinforcing that.”

THE VALUE OF PROCESS

Anyone watching Evansen would say he’s a fairly fast painter. It’s part of his plein air background.

But painting fast has its own requirements.

“[There’s] an inverse relationship between how quickly you can paint something and how difficult it is to paint fast.”

To paint fast, says Evansen, you need a plan. Evansen’s plan centers on his value study.

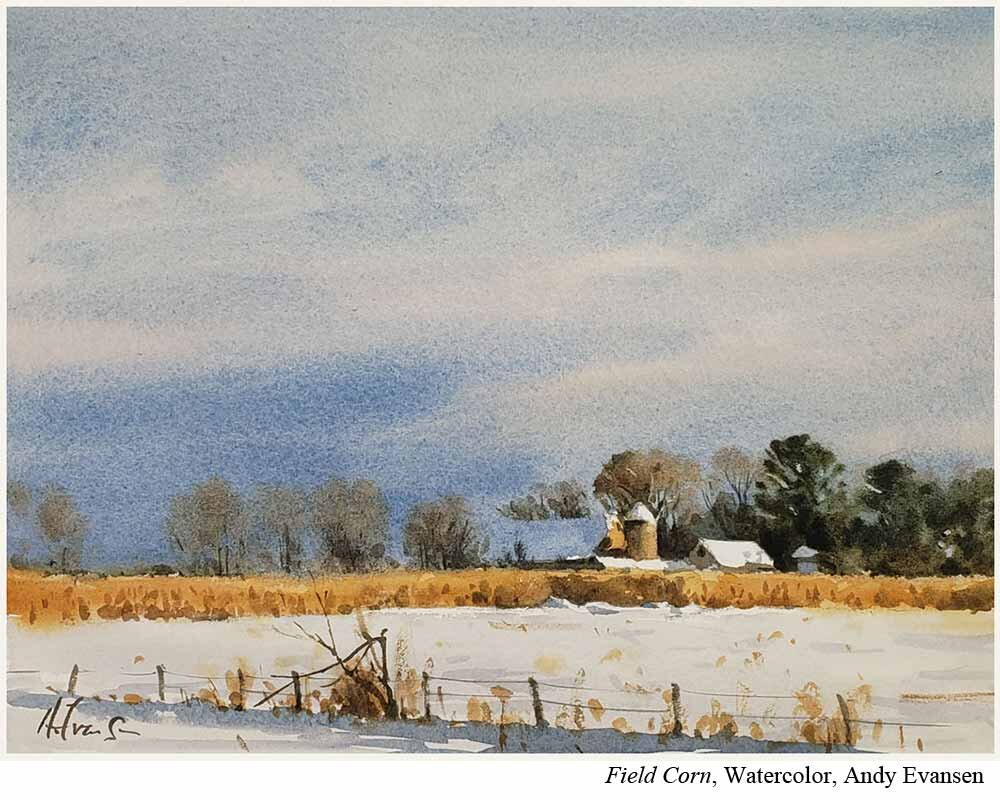

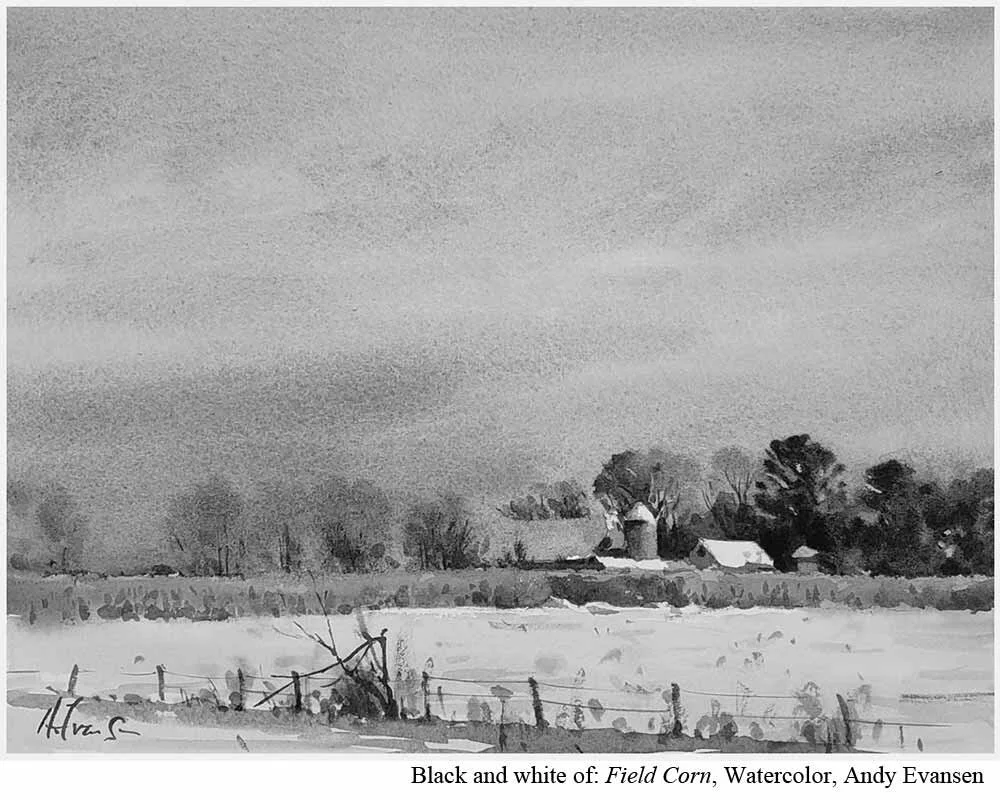

For Evansen, his value study is a small monotone painting using only paynes grey or neutral tint. He paints the study with a brush. He does this for two reasons. First, it’s also his painting warmup. He wants to go through the motions with a brush. Second, he wants to avoid creating shape outlines like a coloring book, which a pencil would do. His aim is to create the shapes themselves.

Evansen plans his value study to have three values: light (which he will leave white), mid tone and dark. He squints at his scene and paints any values that are mid tone or dark in one large shape. He will then go back in with a second wash to make the darkest darks.

Here’s the important piece for that big shape: It’s all connected. He doesn’t paint a tree shape and then another tree shape and then a barn shape staccato like. Anything mid tone or darker gets painted together connected in one big wash. It’s what holds his painting together and will attract the viewer from across the room.

“You have to remember your paintings need to read well from a distance, '' he says. “The big shapes do that. So you’re making sure your painting will grab someone’s attention from far away when you concentrate on big, interesting shapes.”

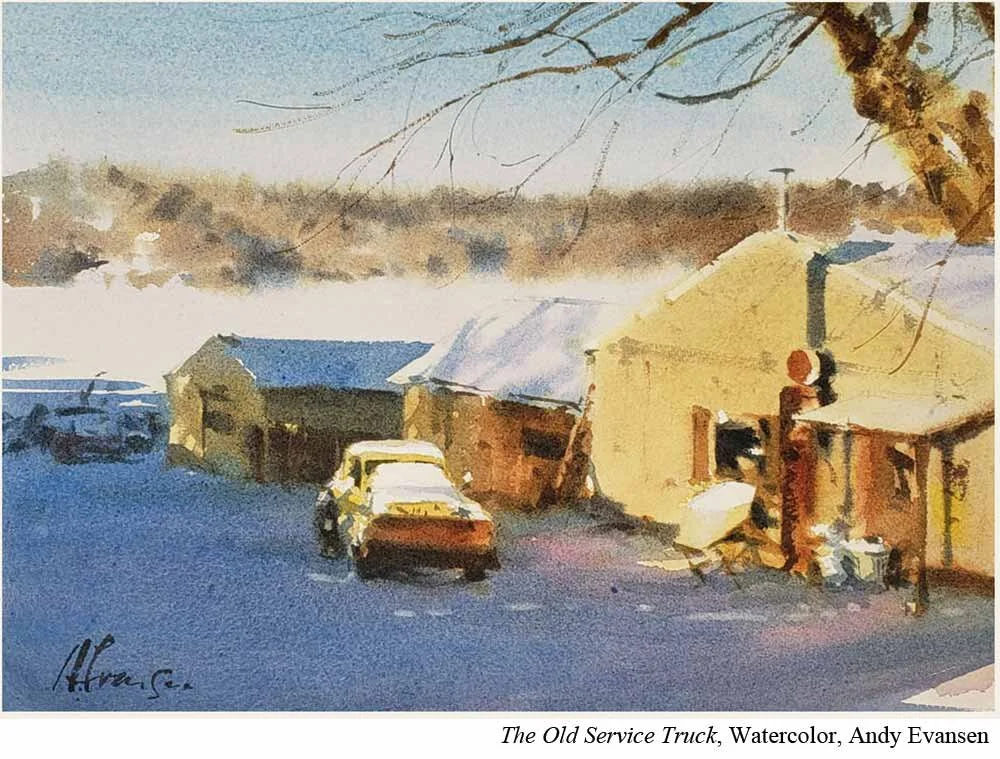

He can go back in with a second and final wash to punch up his darkest darks and create hard edges necessary to draw the viewer to a focal area.

This can be a tricky concept to understand. Even for established painters.

The value study helps him not only create big interesting shapes that will attract viewers from across the room. They also help him make sure that his area of interest is pulling the eye and that his composition doesn’t need any adjustments.

Once he’s confident in his value study, he can go to the full color painting.

FULL COLOR

When it’s time to paint the full color painting, he can be confident his painting will work from a composition standpoint.

Evansen loosely draws his drawing onto his watercolor paper, wets the paper, and begins much like he did with his value study. Only this time, he starts with lightest values and begins painting top to bottom.

He works with local color and paints wet into wet.

Then comes the middle value state. And it’s tricky.

“That’s by far the most difficult stage of the painting because that's the first time you’re painting things and objects. So your brain goes into separation mode. Instead of connections you're seeing in cars and trees.”

This is when the importance of that value study comes in. Evansen can turn off his brain and trust the thinking he’s done prior. He follows his value study, and he paints it almost exactly like his value study. He’s connected all those mid value shapes. Instead of painting it all with paynes grey, he’s using local color. But again, it’s all connected.

“With a medium like watercolor that's so fluid and all those beautiful passages you get with lost edges, that’s where the beneficial part of the values studies come in.”

This is where Evansen’s realism and impressionism meet in the most beautiful of ways. He works primarily with the colors he sees in the scene (local color) but he continues to connect mid value shapes.

For example, if a car shape is next to a tree shape, he will paint the car shape red and then go directly into the green of the tree shape making sure the paint physically touches so there’s a soft blend between the two.

Later, in his final layer, he can go back and add hard edges and make things darker. But he wants to make sure he chooses very consciously where he does that.

And he does. After he finishes that mid tone wash, Evansen lets the painting dry a bit. Finally, he’ll go back in and use hard edges and dark values to direct the viewer’s eye. The result is a painting that is loose and impressionistic but still reads as representative. It gives the viewer a chance to be a participant in the painting by adding her own ideas about what she sees in.

Evansen developed his process because he knows he has tendencies to get tight. He also knows that sometimes you have to just have faith in the process.

“We're fighting the organized brain,” he says. Our natural tendency to want these paintings to start looking good, early and not trusting the process.”

Check out my interview with watercolorist Andy Evansen (Ep. 12) here. If you want new episodes and articles sent straight to your inbox, add your name to the newsletter list below.